Price Stabilisation

Price stabilisation

Many primary markets are subject to extreme fluctuations in price. There are several methods of intervention available to governments and agencies.

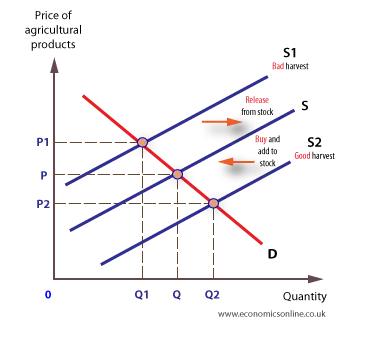

Buffer stocks

Buffer stocks are stocks of produce which have not yet been taken to market. They can help stabilise prices by taking surplus output and putting it into a ‘store’, or, with a bad harvest, stock is released from storage.

A target price can be achieved through intervention buying and selling.

Ceilings and floors

The buffer stock managers are likely to establish a price ceiling, above which intervention selling will occur, and a price floor, below which intervention buying will take place.

Evaluation of buffer stocks

While buffer stocks can help stabilise price, there are several disadvantages, including:

- Additional costs to society, such as building costs, extra storage, insurance and costs of managing the scheme.

- Furthermore, some commodities cannot easily be stored because they are perishable.

- The system relies on starting with a good harvest, indeed, without stocks in the system it is not possible to react to a poor harvest.

- Buffer stocks do not prevent the initial problem from arising.

- Critics argue that they distort the operation of free markets and prevent the price mechanism working effectively.

- Finally, there is the potential problem of moral hazard, which means that buffer stocks provide an insurance against poor harvests and may encourage producers to be inefficient.

Guaranteed prices

Guaranteeing a price to producers (at P1 in the diagram below), irrespective of the output they produce, is another way of stabilising prices and incomes.

A government or agency can establish a target price, and then guarantee to pay farmers and growers this price, whatever output is produced. If the market price rises above this guarantee, the market price will prevail. But if the market price falls below the guarantee, then the guaranteed price will prevail.

However, they can also be criticised because:

- They encourage over-production creating a surplus of Q2 to Q1.This problem is particularly associated with the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

- They can promote inefficiency. For example, farmers may question whether it is worth bothering to be efficient if they are guaranteed a buyer.

- There are also extra costs of storage or disposal.

Set-Aside programmes

Set-aside schemes involve farmers and growers being paid to take land out of production, and are used widely in the EU and USA. Set-aside can be effective because it can prevent surpluses happening in the first place, and hence avoid storage, distribution and management costs.

Export subsidies

An export subsidy involves producers being paid a subsidy to export their surpluses at artificially low prices. However, other countries may retaliate, and protect their own producers from cheap imports, because it can be argued that export subsidies are a form of unfair competition.

Quotas

Over-production can be controlled by allocating production quotas to producers. Quotas are agreed quantities that individual producers must produce, and a quota system can help prevent over or under production in response to economic shocks.

Better information about future shocks

Another way to stabilise markets is to encourage producers to make better use of the internet and computer technology to predict the weather. This enables farmers and growers to predict the onset of other potential shocks so that they can react quickly. In addition, specialist knowledge and skills can also be acquired by studying agricultural courses at specialist colleges.

The Common Agricultural Policy

The EU protects its farmers and growers through its Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). Through the CAP, European farmers receive annual subsidies of around £30 billion each year.

The evolution of CAP

CAP was created by the Treaty of Rome (1957) to ensure food supplies for Europe, and provide a fair income for European farmers. Price support schemes, such as guaranteed prices, were first introduced in 1962, and became the main means of supporting European farmers.

By the mid 1980s, over-production created massive surpluses and this led to major reforms, including the use of set-aside programmes.

By the early 1990s, there was a movement away from guaranteed prices towards direct subsidies to farmers, irrespective of the output they produced.

The Fischler Reforms, of 2003, continued the process of decoupling subsidies and farm output, and introduced a ‘green’ element to CAP, forcing farmers to meet environmental and animal welfare standards.

The UK receives a controversial rebate against payments into the EU to compensate for that fact that it receives relatively little income from CAP in comparison with France and Spain.

SOURCE: THE TIMES, JUNE 2005

Farming subsidies in the EU are based on the size of farms, so countries with the largest farms gain the most.

France takes the biggest slice of the subsidies, with Spain and Germany a distant second and third. French farmers receive, on average, approximately €17,000 per capita.

Because the UK derives such a low proportion of its national income and employment from farming, it is given a rebate as compensation.