Monopoly power

Monopoly power

A pure monopoly is defined as a single supplier. While there only a few cases of pure monopoly, monopoly ‘power’ is much more widespread, and can exist even when there is more than one supplier – such in markets with only two firms, called a duopoly, and a few firms, an oligopoly.

According to the 1998 Competition Act, abuse of dominant power means that a firm can ‘behave independently of competitive pressures’. See Competition Act.

For the purpose of controlling mergers, the UK regulators consider that if two firms combine to create a market share of 25% or more of a specific market, the merger may be ‘referred’ to the Competition Commission, and may be prohibited.

Formation of monopolies

Monopolies are formed under certain conditions, including:

- When a firm has exclusive ownership or use of a scarce resource, such as British Telecom who owns the telephone cabling running into the majority of UK homes and businesses.

- When governments grant a firm monopoly status, such as the Post Office.

- When firms have patents or copyright giving them exclusive rights to sell a product or protect their intellectual property, such as Microsoft’s ‘Windows’ brand name and software contents are protected from unauthorised use.

- When firms merge to given them a dominant position in a market.

Maintaining monopoly power – barriers to entry

Monopoly power can be maintained by barriers to entry, including:

Economies of large scale production

If the costs of production fall as the scale of the business increases and output is produced in greater volume, existing firms will be larger and have a cost advantage over potential entrants – this deters new entrants.

Predatory pricing

This involves dropping price very low in a ‘demonstration’ of power and to put pressure on existing or potential rivals.

Limit pricing

Limit pricing is a specific type of predatory pricing which involves a firm setting a price just below the average cost of new entrants – if new entrants match this price they will make a loss!

Perpetual ownership of a scarce resource

Firms which are early entrants into a market may ‘tie-up’ the existing scarce resources making it difficult for new entrants to exploit these resources. This is often the case with natural monopolies, which own the infrastructure. For example, British Telecom owns the network of cables, which makes it difficult for new firms to enter the market.

High set-up costs

If the set-up costs are very high then it is harder for new entrants.

High ‘sunk’ costs

Sunk costs are those which cannot be recovered if the firm goes out of business, such as advertising costs – the greater the sunk costs the greater the barrier.

Advertising

Heavy expenditure on advertising by existing firms can deter entry as in order to compete effectively firms will have to try to match the spending of the incumbent firm.

Loyalty schemes and brand loyalty

If consumers are loyal to a brand, such as Sony, new entrants will find it difficult to win market share.

Exclusive contracts

For example, contracts between specific suppliers and retailers can exclude other retailers from entering the market.

Vertical integration

For example, if a brewer owns a chain of pubs then it is more difficult for new brewers to enter the market as there are fewer pubs to sell their beer to.

Evaluation of monopoly

Following Adam Smith, the general view of monopolies is that they tend to seek out ways to increase their profits at the expense of consumers, and, in so doing, generate more costs to society than benefits.

The costs of monopoly

Less choice

Clearly, consumers have less choice if supply is controlled by a monopolist – for example, the Post Office used to be monopoly supplier of letter collection and delivery services across the UK and consumers had no alternative letter collection and delivery service.

High prices

Monopolies can exploit their position and charge high prices, because consumers have no alternative. This is especially problematic if the product is a basic necessity, like water.

Restricted output

Monopolists can also restrict output onto the market to exploit its dominant position over a period of time, or to drive up price.

Less consumer surplus

A rise in price or lower output would lead to a loss of consumer surplus. Consumer surplus is the extra net private benefit derived by consumers when the price they pay is less than what they would be prepared to pay. Over time monopolist can gain power over the consumer, which results in an erosion of consumer sovereignty.

Asymmetric information

There is asymmetric information – the monopolist may know more than the consumer and can exploit this knowledge to its own advantage.

Productive inefficiency

Monopolies may be productively inefficient because there are no direct competitors a monopolist has no incentive to reduce average costs to a minimum, with the result that they are likely to be productively inefficient.

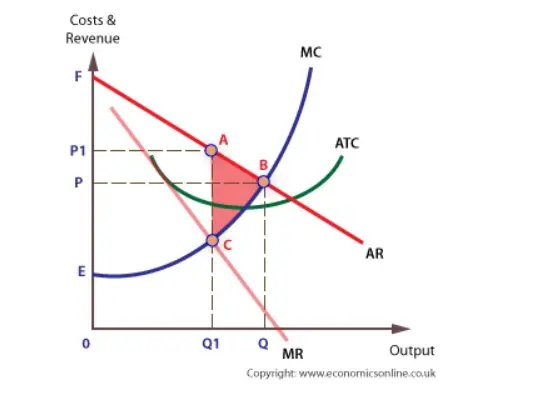

Allocative inefficiency

Monopolies may also be allocatively inefficient – it is not necessary for the monopolist to set price equal to the marginal cost of supply. In competitive markets firms are forced to ‘take’ their price from the industry itself, but a monopolist can set (make) their own price. Consumers cannot compare prices for a monopolist as there are no other close suppliers. This means that price can be set well above marginal cost.

Net welfare loss

Even accounting for the extra profits derived by a monopolist, which can be put back into the economy when profits are distributed to shareholders, there is a net loss of welfare to the community. Welfare loss is the loss of community benefit, in terms of consumer and producer surplus, that occurs when a market is supplied by a monopolist rather than a large number of competitive firms.

A ‘net welfare loss’ refers any welfare gains less any welfare loses as a result of an economic transaction or a government intervention. Using ‘welfare analysis’ allows the economist to evaluate the impact of a monopoly.

Less employment

Monopolists may employ fewer people than in more competitive markets. Employment is largely determined by output – the more output a firm produces the more labour it will require. As output is lower for a monopolist it can also be assumed that employment will also be lower.

The benefits of monopoly

Monopolies can provide certain benefits, including:

Exploit economies of scale

If the firm exploits its monopoly power and grow large it can also exploit economies of large scale. This means that it can produce at low cost and pass these savings on to the consumer. However, there would be little incentive to do this and the savings made might be used to increase profits or raise barriers to entry for future rivals.

Dynamic efficiency

Monopolists can also be dynamically efficient – once protected from competition monopolies may undertake product or process innovation to derive higher profits, and in so doing become dynamically efficient. It can be argued that only firms with monopoly power will be in the position to be able to innovate effectively. Because of barriers to entry, a monopolist can protect its inventions and innovations from theft or copying.

Avoidance of duplication of infrastructure

The avoidance of wasteful duplication of scarce resources – if the monopolist is a ‘natural monopoly’ it can be argued that competitive supply would be wasteful. Natural monopolies include gas, rail and electricity supply. A natural monopoly occurs when all or most of the available economies of scale have been derived by one firm – this prevents other firms from entering the market. But having more than one firm will mean a wasteful duplication of scarce resources.

Revenue

Monopolists can also generate export revenue for a national economy. A single firm may gain from economies of scale in its own domestic economy and develop a cost advantage which it can exploit and sell relatively cheaply abroad.

Remedies for monopoly

If a monopolist can gain a foothold in a market it becomes very difficult for new firms to enter, with the result that the price mechanism is restricted from doing its job. Resources cannot be allocated to where they are most needed because the monopolist can erect barriers to other firms. These barriers will not ‘naturally’ come down.

The failure of markets to ‘self regulate’ is at the heart of monopoly as a ‘market failure. There are a number of ways in which the negative effects of monopoly power can be reduced:

Regulation of firms who abuse their monopoly power. This could be achieved in a number of ways, including:

Price controls

Setting price controls. For example, the current UK competition regulator, the Office of Fair Trading (OFT), has developed a system of price ‘capping’ for the previously state owned natural monopolies like gas and water. This price capping involves tying prices to just below the current general inflation rate. The formula, RPI – X, is used, where the RPI (the Retail Price Index) is the chosen index of inflation and ‘X’ is a level of price reduction agreed between the regulator and the firm, based on expected efficiency gains.

Prohibiting mergers

Prohibiting mergers – in the UK the Competition Commission can prohibit mergers between firms that create a combined market share of 25% or more if it believes that the merger would be against the ‘public interest’. In making their judgment, the ‘public interest’ takes into account the effect of the merger on jobs, prices and the level of competition.

Breaking up the monopoly

Breaking up the monopoly into several smaller firms. For example regulators in the EU are currently investigating potential abuse of market dominance by Microsoft, which is under threat of being broken up into two companies – one for its operating systems and the other for software.

Nationalisation

Bringing the monopoly under public control – which is referred to as ‘nationalisation’. The ultimate remedy for an abusive monopoly is for the State to take a controlling interest in the firm by acquiring over 50% of its shares, or to take it over completely. The monopolist can still be run along commercial lines, but be made to operate as though the market were competitive.

De-regulation

In those cases where a monopolist is already State controlled, such as the Post Office, it may be necessary to engage in deregulation to enable it to become more efficient. Deregulation could be used to bring down barriers to entry and open up a previously state controlled industry to competition, as has happened with the British Telecom and British Rail monopolies. This may help encourage new entrants into a market.

large number of competitive firms