Inflation and deflation

Inflation and deflation

Inflation and deflation arise from changes in either the demand side or supply side of the macro-economy.

Demand pull inflation

Demand pull inflation usually occurs when there is an increase in aggregate monetary demand caused by an increase in one or more of the components of aggregate demand (AD), but where aggregate supply (AS) is slow to adjust.

The commonest causes are demand shocks, such as:

- Earnings rising above factor productivity.

- Cheaper credit, following a reduction in interest rates.

- Excessive public sector borrowing.

- A housing boom creating equity withdrawal and a positive wealth effect.

- Changes in the savings ratio.

The savings ratio

The savings ratio indicates the percentage of disposable income which is saved, rather than spent. Sudden changes in the savings ratio are an indicator of future changes in spending and AD, and can be a prelude to inflation or deflation.

A rise in the savings ratio indicates a decline in consumer confidence, whereas a fall in the savings ratio indicates a rise in confidence and spending, which can trigger an increase in the price level.

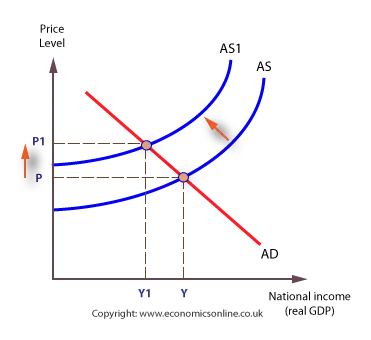

Cost-push inflation

Cost-push inflation occurs when an economy experiences a negative cost shock.

An increase in costs causes the aggregate supply curve to shift upward and to the left, resulting in a rise in the price level, and a contraction of aggregate demand.

The commonest causes are:

- Oil price shocks, caused by wars or decisions by OPEC to restrict output.

- Increases in farm prices or general food prices, following a series of poor harvests.

- Rapidly rising wage costs.

- A fall in the exchange rate, which increases the price of all imports.

- Imported cost push inflation as a result of inflation in other parts of the world.

A fall in the exchange rate

A reduction in the exchange rate will mean that more Sterling is required to purchase a given quantity of imports; in other words, the price of imports will rise. After a time-lag, this will feed its way into retail prices. For example, a motor vehicle imported from Germany for €50,000 would cost £25,000 at an exchange rate of £1 – €2. If Sterling falls in value, to £1 = €1.90, then the Sterling price would rise to £26,316.

Given that approximately 35% of the CPI basket of consumer goods and services are imports, the effect of a fall in the exchange rate is to raise the CPI. In addition, imported raw materials are also more expensive so costs of production will rise for those firms that source their inputs from abroad. Therefore, while a low exchange rate may be beneficial for exports, it has as a potentially inflationary effect on costs and prices.

Research by the Bank of England has identified two phases through which a change in the exchange rate ‘passes through’ the economy.

- In phase one, a change in the exchange rate affects import prices fairy quickly.

- In phase two, changes in import prices work their way into retail prices. Phase two may take much longer, even up to 3 years to complete.

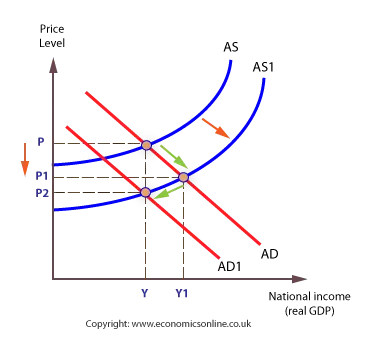

Causes of deflation

Deflation tends to occur when the economy’s capacity, as indicated by the position of the AS curve, grows at a faster rate than AD. Firms have to cut prices in order to stimulate sales and get rid of stocks.

Deflation can be triggered by an increase in supply. As business and consumer confidence in the economy declines, AD falls, resulting in recession.

Recent UK Inflation

Go to: Measuring inflation