Trade creation

Trade creation

When customs unions are established the flow of trade between countries involved in the new union and those outside will be affected. Customs unions eliminate barriers to trade between members, which is assumed to provide a considerable incentive to increase trade between members and to reduce trade between members and non-members. It is often easiest to appreciate the effect of a customs union by considering what happens when one country joins an existing union.

Outside a union, and operating independently, a single nation will look to exploit its comparative advantage. In a free trade environment, countries will trade with who they like, attempting to exploit their own comparative cost advantage through specialisation. They will export goods they produce most efficiently, and import goods from low-cost countries who have exploited their own comparative cost advantage to produce cheap exports. In a situation where countries do not trade freely, by imposing tariffs, or by favouring one country over another in terms of tariff levels, trade will be distorted and the pattern of trade will change. Inefficient producers may be protected and encouraged, at the expense of more efficient imports.

The creation of a customs union, with common external tariffs, will further alter the existing pattern of trade flows. The assumption is that before the union, members imposed differential tariffs on different countries to protect their own industries. Taking a hypothetical example from an actual historical period, we shall assume that, prior to joining the European ‘common market’ in 1973, the UK could produce butter at 130p per kilograms (kg), on average. At the same time, New Zealand could produce the same quantity for 100p, and Denmark could produce it for 120p. Hence, prior to the formation of a customs union, New Zealand has a comparative advantage in butter, and is the most efficient. Denmark is the second most efficient producer, and the UK is the least efficient.

Let us assume that, in order to protect its inefficient farmers equally, the UK imposes differential tariffs on New Zealand and Denmark in order to raise the imported price above its own (high cost) butter. For example, imposing a high 32% tariff on ‘very’ low priced New Zealand butter would raise its price to 132p per kg (100p to 132p), as would imposing only a 10% tariff on low priced Danish butter (120p to 132p). We will also assume that, with these tariffs in place, a total demand of 30m kg of butter exists in the UK each year, with UK farmers supplying 20m kg (the maximum it can produce), and New Zealand and Danish farmers supply 5m kg each.

Once a union is created, members agree to eliminate tariffs between themselves. The effect of this is that, facing lower priced, zero-tariff, imports from members, consumers increase their demand for these goods, and new trade will be created – a process called trade creation. The terms trade creation and trade diversion are closely associated with Chicago School economist Jacob Viner (The Customs Union Issue, 1950).

For example, if Denmark and the UK form a customs union, tariffs on Danish butter must now be reduced, and once they are completely removed, the free market price of 120p will be highly attractive to UK consumers. UK consumers will now consume more butter in total because average butter prices will have fallen with the removal of tariffs on Danish butter, and total demand for butter rises. For example, total output and consumption might increase to 32m kgs (up by 2m), with UK farmers down from 20m to 15m, New Zealand exports collapsing to just 2m, and Denmark increasing its output and sales of butter to the UK to 10m (from 5m to 10m). Total consumption has gone up from 30m (20 + 5 + 5), to 32m (15 + 2 + 15). The additional 2m kgs of butter produced and consumed is the new trade created as a result of the removal of barriers by union members.

Furthermore, this will enable a dynamic reaction within Denmark and the UK. Over time, as countries (Denmark and the UK) become more integrated, increased trade will generate further efficiency gains, such as through the application of economies of scale. Prices may fall even further, relative to those of non-member countries, and the process of trade creation continues. For example, with increased sales, Denmark can specialise further in butter production, and produce on large scale, bringing prices down even further (perhaps nearer to the New Zealand level). Also, the UK can now free up its resources, and move them out of butter production and into goods and services for which the UK has a comparative advantages over Denmark. Hence, over time, trade creation will continue as a positive long-term effect of a customs union.

The major loser in this is the previous trading partner left outside the bloc – less trade now exists between new members and their old trading partners. The process of efficient producers losing out to inefficient ones is generally referred to as trade diversion. For example, after Denmark and the UK form a customs union, New Zealand, which was the most efficient butter producer, suffers a loss of sales to the UK, from 5m to 2m, with trade diverted from New Zealand to Denmark. However, there is some debate about the use of the term trade diversion. In its simplest form it means any trade diverted away from efficient global producers as a result of the creation of a customs union. Other economists regard trade diversion as relating to the long-term loss of trade resulting from inefficient producers (such as Denmark, in our hypothetical example) becoming more efficient following membership of the union. For example, if the price of Danish butter falls from 120p to 95p as a result of trade expansion within the union, it is now 5p cheaper than New Zealand in the open market, and more trade may now be diverted away from the formerly highly efficient New Zealand. Whichever definition is accepted, it is clear that in this case the union has distorted trade.

Finally, we also need to consider the loss of tariff revenue that might follow the diversion of trade from non-member countries. Given that, in our simple example, imports from New Zealand have fallen causing a loss of tariff revenue, and tariff revenue from Danish butter has been eliminated, it is necessary to weigh up the welfare gains and losses from the formation of the customs union. There is no simple answer to this, and it is quite possible that a union could result in either a net loss, or a net gain.

We can conclude that small countries (such as New Zealand, in our hypothetical case) may be at a considerable disadvantage by not joining a customs union, or free trade area. In fact, they are certainly likely to, as the above analysis would indicate. Indeed, New Zealand is a key partner in the Cairns group, which was formed in 1986 by 14 agricultural exporting countries, largely as a response to increased European protection associated with its Common Agricultural Policy (CAP).

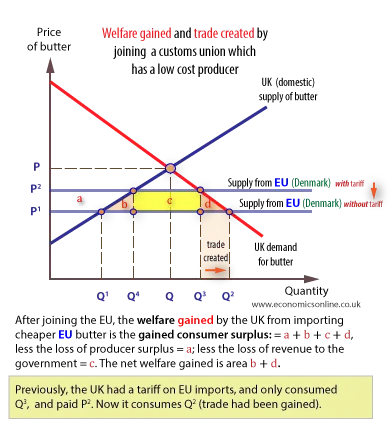

Trade creation diagram

With a tariff imposed prior to the formation of a customs union with Denmark, UK farmers supply 0 – Q2, and Q2 to Q3 is imported. The net welfare loss would be X + Y.

Following the union, the tariff is abandoned and the market share of UK farmers falls to 0 – Q1, and imports from Denmark increase from Q4 – Q3, to Q1 to Q2. The welfare gain is X + Y, and the trade created is Q3 to Q2.

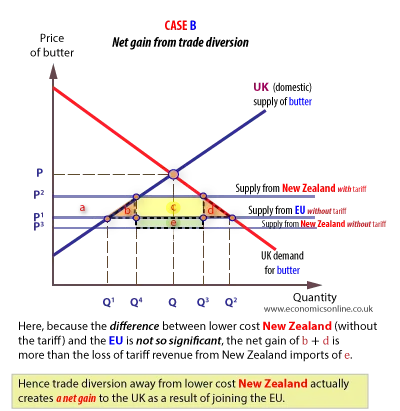

Trade diversion diagrams