Producer supply

Supply

Production is the process of turning inputs of scarce resources into an output of goods or services. The role of a firm is to organise scarce resources to satisfy consumer demand in a profitable way. Supply is defined as the willingness and ability of firms to produce a given quantity of output in a given period of time, or at a given point in time, and take it to market. Not all output is taken to market, and some output may be stored and released onto the market in the future.

Supply can be measured for a single factor of production, for a single firm, for an industry and for the whole economy.

Determinants of supply

Price

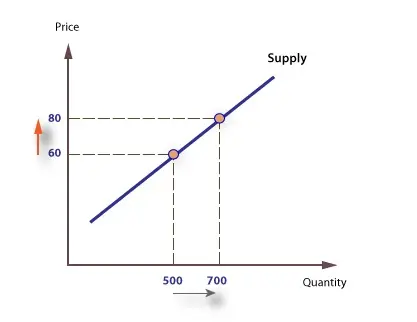

The price of the product is the starting point in building a model of supply. The supply model assumes that price and quantity supplied are directly related.

Non-price factors

As well as price, there are several other underlying non-price determinants of supply, including:

The availability of factors of production

The availability of factors of production, such as labour or raw materials, can affect the amount that can be produced and supplied. For example, if a firm producing motor vehicles experiences a shortage of steel for its body panels, then its ability to produce vehicles will be reduced.

Cost of factors

Changes in costs will alter a firm’s calculation of how much to supply at a given price. For example, if the same motor manufacturer experiences an increase in labour costs due to an increase in the wage rate, the cost of producing each vehicle will rise. This means that the price the manufacturer expects to receive will increase. If the price does not increase, less will be produced, ceteris paribus.

New firms entering the market

In terms of total supply to a market, the number of firms in the market will affect the total supply. New firms in a market will increase market supply and firms leaving will reduce supply. New firms may be attracted into a market because of the expectation of profits and existing firms may leave because they cannot cover their costs, and make losses. They may also leave because they cannot cover their opportunity cost, meaning that leaving becomes the best alternative.

Weather and other natural factors

Changes in the weather can have a considerable impact on the ability to produce certain products, like farm produce and commodities. This tends to affect the primary sector more than manufacturing.

Taxes on products

Taxes on products, such as Value Added Tax (VAT), have a direct effect on supply. An indirect tax imposed on a product has an effect similar to that of a cos. which means that increased taxes affect a producer’s decision to supply, and how much to supply.

Subsidies

Subsidies are funds given to firms to enable them to increase their supply or to reduce the price of their product to the consumer. Subsidies can alter the firm’s willingness and ability to produce and supply.

Supply and price

Supply schedules

A supply schedule shows the relationship between price and planned supply over a hypothetical range of prices. For example, this supply schedule shows how many cans of cola would be supplied by a school or college canteen in a single week.

| PRICE (p) | QUANTITY SUPPLIED |

| 80 | 2000 |

| 70 | 1800 |

| 60 | 1600 |

| 50 | 1400 |

| 40 | 1200 |

| 30 | 1000 |

| 20 | 800 |

| 10 | 600 |

| 0 | 400 |

The higher the price, the greater the quantity supplied. A supply curve is derived from a supply schedule. The upward slope of a supply curve illustrates the direct relationship between supply decisions and price. In this case, the supplier of cola would supply 400 more cans at 80p compared with 60p.

Mathematically, the supply schedule can be derived from a supply function, and in this case the supply function is Qs = 400 + 20p.

Why do supply curves slope upwards?

There are a number of explanations of this relationship, including the law of diminishing marginal returns.

The Law of diminishing returns

The law of diminishing marginal returns explains what happens to the output of products when a firm uses more variable inputs while keeping a least one factor of production fixed. Real capital, such as buildings, machinery, and equipment, is usually the factor kept fixed when demonstrating this principle.

Economic theory predicts that, when employing these extra variable factors, such as labour, the marginal returns (additional output) from each extra unit of input will eventually diminish.

Take, for example, a hypothetical firm that has a factory in which computers are assembled. The machinery is fixed, and extra workers can be hired to increase the output of assembled computers. At first, the addition of extra workers creates a significant benefit because it becomes possible to divide up the labour, and for workers to specialise in undertaking one task. Initially, there are increasing marginal returns to each additional worker.

However, marginal returns will eventually fall because the opportunity to divide labour and to specialise must eventually ‘dry up’. Gradually, each additional worker contributes less than the one before so that total output of computers continues to rise, but at a decreasing rate. The falling marginal returns from each successive worker leads to a rise in the cost of using them.

Diminishing returns and increasing costs

Firms need to sell their extra output at a higher price so that they can pay the higher marginal cost of production. Hence, decisions to supply are largely determined by the marginal cost of production. The supply curve slopes upward, reflecting the higher price needed to cover the higher marginal cost of production. The higher marginal cost arises because of diminishing marginal returns to the variable factors.

Go to shifts in supply.