Primary markets

Primary markets

Commodity and primary markets

Primary products are extracted directly from the earth, and include grains, fuels, textiles, gems and minerals. Most primary products are bought and sold in international commodity markets, such as the London Metal Exchange, and the Chicago Mercantile Exchange. Primary production is immensely varied and includes small-scale producers as well as multinationals like BP, Texaco, and Rio Tinto.

Spot and future markets

Primary commodities are bought and sold in spot and futures markets. In spot markets, sellers have existing stocks to sell, and buyers expect immediate delivery, or in the very near future. Prices in spot markets reflect the interaction of buyers and sellers who use all available information to bid, offer and accept prices and settle debts in a short space of time, on-the-spot. The process has been described as price discovery, with price offers and bids converging until a price is fixed.

In futures markets, delivery and payment is not on-the-spot, but at some agreed point in the future, such as in three months time. Prices are determined in a similar way to spot prices, the difference being that final settlement and delivery occur in the future, and contracts can be resold before maturity, creating the possibility of a speculative gain. The main advantage is that buyers and sellers can ‘lock in’ current prices and reduce risks. (Source: Levinson, M, 1999: Guide to The Financial Markets, The Economist.)

Most commodities have both types of market in operation, though many are dominated by futures trading. For example, in the market for cocoa, large confectionery manufacturers like Nestle and Mars use futures contracts to try to ensure price stability in the future. The largest futures markets for commodities like cocoa, coffee, and tea, are based in Chicago, London, and New York.

The market for agricultural products

The market for agricultural commodities is significant and widely studied in economics. This is because foods and beverages are an important primary product and because agricultural markets have some very special characteristics.

Demand

The demand for agricultural products has a number of special characteristics, including the following:

- In advanced economies, demand tends to be stable over time, given the stability of the population of large consuming economies like the USA and EU countries.

- Demand in advanced economies also tends to be very price inelastic because food and drink products are necessities, and demand is not dependent on price.

- Demand is also very inelastic with respect to income, with many foods being inferior goods.

Supply

All countries attempt to produce as much food as they can from the land they have, and the climate they face. To satisfy the need for food security, many national governments support their farmers and growers with subsidies other assistance. Despite this, global food production is often unpredictable, and supply is unstable. Food production and supply takes place under the following general conditions:

- Farmers and growers are often extremely small-scale enterprises using unsophisticated production techniques. For example, coffee growers in Brazil and cocoa producers in Ghana commonly employ fewer than 20 people, using methods unchanged for hundreds of years.

- Food production is widely dispersed throughout a country and is not localised, meaning that co-ordination of production is difficult.

- Supply is usually very elastic in the long run because it is easy to convert land to different crops. Hence, an increase in the price of one crop on world markets will encourage producers to switch to that crop. However, supply is perfectly inelastic in the short run. Once crops are planted, or livestock is bred, supply cannot be increased until the next season.

- Supply is subject to random supply shocks, such as droughts and floods, diseases and wars. This means that sudden shortages, or unplanned gluts, can create considerable price instability. Furthermore, there is imperfect knowledge about these supply shocks. Accurately predicting the onset of bad weather or disease is impossible, and this makes planning very difficult, so farmers often focus their efforts on the current year, rather than thinking ‘long term’.

- There is limited feedback to farmers on the effect of their own actions on the market price. Farmers and growers cannot always see or measure the impact of their decisions to increase or decrease output on the market price. For example, a shortage in one year will raise the world price, and encourage producers to increase output in the following year. However, the increase in output will cause the price to fall, leaving farmers worse off.

The problems faced by farmers and growers

Because of the conditions of demand and supply described above, farmers and growers typically face three main problems:

- Firstly, prices can be extremely unstable in the short run, triggered by unplanned changes in supply caused by unusually good or bad harvests.

- Secondly, many producers face falling incomes in the long run, making farming and growing increasingly unprofitable. This is commonly caused by an increase in global production in the long run. However, low incomes will discourage production in the future and jeopardises food security, which is why farmers and growers in most countries are given support.

- Thirdly, there has been a gradual, yet significant, reduction in bargaining power of farmers and growers when it comes to their dealings with large supermarket chains at the national level, and multinational companies at the global level. Increasingly, supermarket chains and multinationals can dictate prices and terms of business to small suppliers, making them unprofitable.

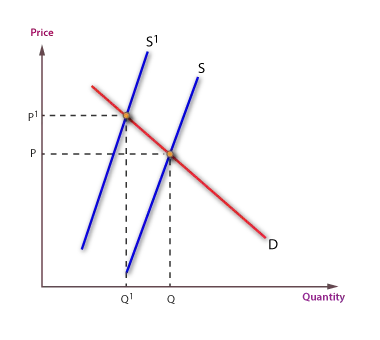

The effects of a bad harvest

An unexpectedly bad harvest will raise price, and an unexpectedly good harvest will depress price.

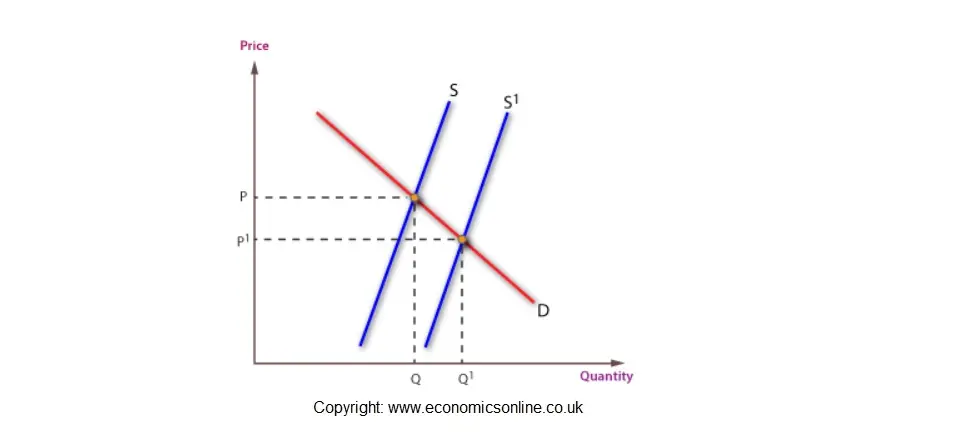

The effects of good harvest

An unexpectedly good harvest, which shifts the short run supply curve to the right, will depress prices.

Go to: Price instability

Go to: The market for oil.html