Shipping containers at a port.

Game Theory in Trade Negotiations: Lessons from the US-China Trade War

We have seen in recent developments that many politicians look at international trade negotiations as being like a game they must win. President Trump, for instance, has complained, “They have to balance out their trade, number one. We have deficits with almost every country — not every country, but almost — and we’re going to change it.” The US has had a trade deficit with China for many years ($295 billion in 2024). As a result, one of Trump’s first actions during this term in office was to introduce a 10% tariff on Chinese imports. How do economists look at the situation? Game theory can provide insight.

What’s Game Theory?

Game Theory was first postulated in 1838 by French economist and mathematician, Augustin Cournot, and expanded upon by John von Neumann and Oskar Morgenstern in 1944. It examines how people (or organisations) apply strategy to achieve the best results for themselves in some form of competitive activity that involves uncertainty. We have previously written more extensively about game theory, focusing on a case study The Prisoner’s Dilemma.

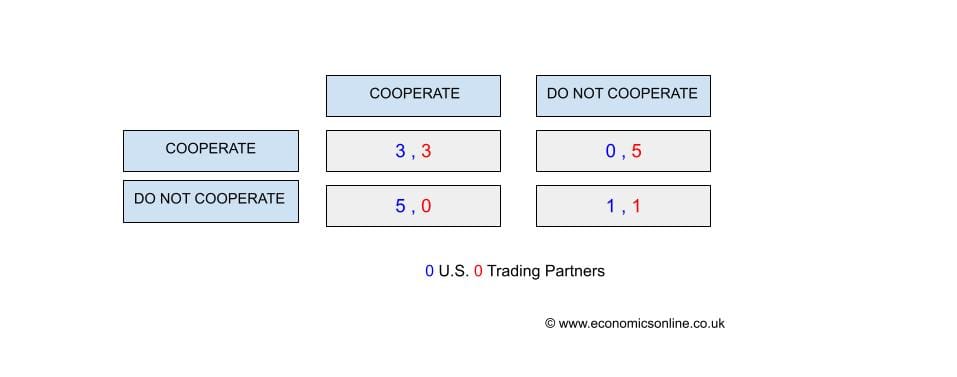

In simple terms, game theory assumes you have two parties, who can either work together on a problem or work for their betterment at the expense of the other party. The best overall result comes from working together. However, either party can receive a higher individual pay-off by working alone (in which case the other party receives an extremely low pay-off, often worse than doing nothing). If both parties opt to work alone there is a middle-level pay-off. The problem is that there is uncertainty, and neither party knows what the other intends to do.

America and International Trade Cooperation – a Focus on Chinese-American Trade

The first Trump administration led a trade war with China in 2018 by announcing a range of tariffs on Chinese exports (beginning with 20% to 50% tariffs on solar panels and washing machines). China, in turn, imposed tariffs on a range of products it was importing from the USA. Over the next few years, both countries imposed various targeted tariffs and made some bilateral agreements. Incoming president, President Biden, chose to keep his predecessor’s tariffs in play and added additional targeted tariffs during his term. In February 2025, the re-inaugurated President Trump increased tariffs on China imports by a further 10%.

The Aspen Economic Strategy Group’s book, Rebuilding the Post-Pandemic Economy examines how the US’s post-pandemic economy could take shape. One area it focuses on is America and international trade cooperation, with a particular reference to US-China trade policy. In this, Chad P Brown (Peterson Institute for International Economics & Center for Economic Policy Research) framed the situation between America and its trading partners in terms of Game Theory.

In this example, we look at countries as being “players” – the USA and its Trading Partners. We will consider China as the Trading Partner here.

We assume that the “game” being played is whether to cooperate over trade policy. Both parties are large importers of goods from the other.

With no cooperation between the trading partners, with each protecting its interests, either or both could introduce self-interest policies like tariffs. If one party plays by the rules, and the other introduces tariffs, then the country with the tariff benefits at the other’s expense. These are the (0.5) and (5,0) positions in the above chart. If both countries introduce tariffs, there are no real winners (or total losers) and we have the (1.1) situation above. This produces the worst overall results from the trading relationship, however. If, on the other hand, both countries cooperate we have the (3.3) situation, giving a reasonable result for each country, and the most optimal results overall. Brown sums this up as “trade agreements involve two countries jointly agreeing to cooperate by tying their hands and refraining from imposing tariff policies that are unilaterally optimal, but jointly suboptimal.”

Tit-For-Tat Strategies in Place in Trade Negotiations

Both China and the US have been invoking tit-for-tat strategies since those first 2018 tariffs. Both countries have been treating their trade negotiations like a giant chess board, invoking, removing, and changing tariffs, reacting to the actions of the other nation. The US brought in its latest 10% tariff on Chinese goods on 4 February 2025, and within minutes China announced targeted tariffs on US imports. President Trump in turn announced a 25% tariff on all steel and aluminium imports into the US. The game has continued since then, with both sides announcing further tariffs as a countermeasure. The tariffs (and counter-tariffs) create mutual economic losses, but both sides are using them to gain negotiating leverage.

The trading partners haven’t just relied on tariffs, either. For example, China has announced an anti-monopoly probe into US-owned Google, and China added PVH, the US owner of designer brands Calvin Klein and Tommy Hilfiger, to their "unreliable entity" list. At one point the US banned (and within 24 hours unbanned) Chinese-owned social app, TikTok.

The Nash Equilibrium

Influential mathematician, John Nash, was a great fan of game theory. He postulated that when no participant could benefit from changing their actions, the participants have reached “Nash Equilibrium.” This assumes that players take the most logical action.

Having started a trade war, neither China nor the US can easily back down without losing ground. The countries were probably at a Nash equilibrium during the Biden years, hence the reluctance to remove tariffs during that time. Now that President Trump has rekindled the trade war, the two countries will have to find a new Nash equilibrium, where both countries feel they have a “fair” trade level. This is unlikely to be at the (3,3) level of full cooperation as shown in the Game Theory matrix, however. Both parties are likely to continue the trade war until some form of diplomacy can help reach a mutual agreement.

Role of Third Parties in Mediating Trade Disputes

Sometimes a country appeals to a third-party actor, like the World Trade Organization (WTO), to become involved in mediating international trade disputes. For example, in 2024 China requested WTO dispute consultations with Canada regarding surtaxes imposed by Canada on certain products of Chinese origin. These included electric vehicles and steel and aluminium products. The US has been a complainant to the WTO 124 times, a respondent 160 times, and a third party in 179 cases.

There are three main stages to the WTO dispute settlement process:

- Consultation between the parties

- Adjudication by panels

- Implementation of their ruling (including countermeasures should the losing party fail to abide by the ruling)

The WTO also operates an appellate body, if one of the parties feels it necessary to appeal the panel’s decision.

President Trump has stated he has little confidence in the WTO, however, believing that the USA endures unfair trade conditions. In his opinion, America "has been treated unfairly by trading partners, both friend and foe".