Greece_rejects_austerity

Greek bailout

August 2015

After a mammoth 16 hour meeting in Brussels Eurozone leaders agreed to provide futher bailout funds to Greece in return for significant reforms to public spending and taxation. Greece will be required to pass relevant laws this week to ensure that the reforms are implemented and the financial package is made available.

Earlier reports

Greece closer to default

Greece closer to default

Greece is quickly running out of time to produce a deal that will satisfy its creditors. The next payment is due on June 30th, but is increasingly likely that this will not be made.

The deadline for an agreement is Thursday (June 18th), when finance ministers of Eurozone countries meet with other creditors, including the IMF, in Luxembourg. Credit rating agencies have now downgraded several banks to CCC – a level which suggests they believe that the most likely outcome is a default.

A deal is required so that more bailout funds can be released. It appears that Greece is demanding a restructuring of the debt as well as refusing to implement all the labour market and pension reforms required by its creditors. Pressure was increased following the walk-out this Thursday by IMF negotiators, who claimed that no progress had been made during its recent talks. As a result of the breakdown in talks, and news that Eurozone leaders were now making plans for a default, shares prices across Europe and the USA tumbled.

Greece agrees bailout extension

Greece has reached an agreement with the Eurozone finance ministers to extend its financial rescue by four months, thereby averting exit from the Eurozone. The deal, which commits Greece to continuing with its reform programme, needs to be ratified by the IMF, ECB and members of the European Commission. Any further public spending outside of that already undertaken, must be agreed by creditors. The Euro picked up on news of the deal, although uncertainty remains.

Greece rejects austerity

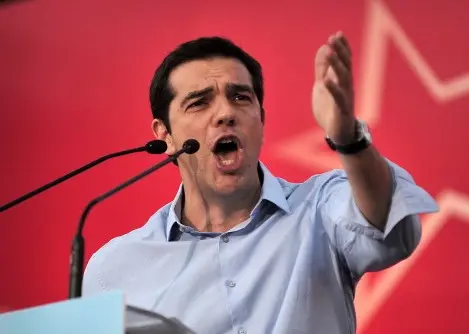

Greece will return the first openly anti-austerity government in the Eurozone when the Syriza party, led by Alexis Tsipras, wins a majority in the 300 seat Parliament in the Greek vote this Sunday. Syriza will oust the New Democracy party of current Prime Minister Antonis Samaras, who became PM in 2012. Technically requiring 40% of the votes, it is likely that a return of 35% will be sufficient, given support from minority anti-euro parties. As counting continued through the night Syriza party edged past the 35% share required to form a government, and is on course for around 150 seats. In response, the euro fell to an 11 year low against the US dollar, down to 1.1098.

Greece will return the first openly anti-austerity government in the Eurozone when the Syriza party, led by Alexis Tsipras, wins a majority in the 300 seat Parliament in the Greek vote this Sunday. Syriza will oust the New Democracy party of current Prime Minister Antonis Samaras, who became PM in 2012. Technically requiring 40% of the votes, it is likely that a return of 35% will be sufficient, given support from minority anti-euro parties. As counting continued through the night Syriza party edged past the 35% share required to form a government, and is on course for around 150 seats. In response, the euro fell to an 11 year low against the US dollar, down to 1.1098.

Tsipras has sought a mandate to renegotiate the terms of the 240 billion euro bailout given the scale of the impact that austerity has had on the Greek economy. While the centre-piece of his election strategy is the reduction in the debt burden, he also wants to raise the Greek minimum wage, increase public sector pay, and put a stop to any further public sector cuts.

Despite stringent cuts, Greek debt has actually increased as a proportion of Greek GDP during 2014, from 146% to 175%. Of course, even with falling debts levels, the significant reduction in GDP since 2009 will have meant that the ratio of debt to income will have actually risen! Although returning to modest growth in 2014, the Greek economy has be shrinking since 2009, and is now just 75% of its economic size prior to the financial crisis. To Greece, it certainly seems that as more debt is repaid, the burden increases and the costs of austerity accelerate. What is clear is that, in addition to successfully getting the message across to the electorate that austerity has simply not worked on any level, Mr Tsipras has provided hope that changes can be made to reverse austerity.

Austerity has been the dominant strategy and accepted wisdom across the developed world as a rational response to the debt crisis, but the lack of growth in many European economies (excluding the UK) as a result has made it increasingly difficult to get debt levels down. Greece is simply experiencing an extreme form of austerity that, most would now agree, was too much for such a fragile economy to cope with – especially one that is not suited to the rigidity that Eurozone membership requires.

Since 2012, when the second Greek bailout was ratified – bringing the total bailout to 240 billion euros – Greece has been in a very tight fiscal straightjacket. Borrowing costs have soared and repayment requirements have been increasingly difficult to meet. With Greece typically relying so much on its public sector, it has been difficult to see where any growth would come from during the years of debt repayment. The financial uncertainty surrounding the 2009 – 2012 period meant that business risks were increasingly difficult to calculate, with the result that private sector Greek investment stagnated. With the fiscal straightjacket in place, and the government unable to devalue and benefit from export led growth, it has been increasingly difficult to see where future growth would come from.

If we take just a few key indicators it is clear that Greece is an economy on its knees, and to many observers, provides a hint of what might be to come for many European economies. In a week that saw the ECB agree to inject a massive 1.1 trillion euros into the Eurozone to avoid deflation, Greece can point to the fact that it has been deflating for some time, with prices falling by 2.5% in the last quarter of 2014, following 16 continuous months of falling prices (ELSTAT). Unemployment is now at a record 28% (December 2014) and over 50% of 16-24 years olds are jobless – it is no real surprise that voters are looking for a change of economic direction. While not committing to a Greek exit, the impact of a Syriza win is the signal it will send to the rest of the Eurozone, and to Europe in general. The consensus – that austerity is a price worth paying to force debtor nations into undertaking structural reforms – has been questioned, if not shattered, in the ‘home of democracy’.

Greece ditched the Drachma, at a rate of 340.75 for 1 euro, back in 2001, to become the 12th member of the Eurozone, despite widespread concerns within and outside Greece about its ability to cope with a fixed exchange rate against the rest of the Eurozone. Indeed, Greece failed in its earlier attempts to meet the criteria laid down for membership, especially in terms of its higher inflation rate, poor productivity and large public sector. Despite some success in controlling inflation and putting the brakes on its burgeoning public sector, for many, the survival of Greece in the Eurozone was always in doubt, with its large public sector, inflexible labour market, and culture of tax avoidance. By 2012 it became increasingly clear that Greece could no longer be sustained within the Euro framework without significant financial support in the form of a second bailout. In the weeks running up to the 2012 election up to one billion Euro was flowing out of Greek banks each day. Although the bailout settled nerves, to many, it simply delayed the inevitable change of government that has now come.

As noted by Matthew Lynn Greek leaders have a long history of economic experimentation ending in disaster. Take one Dionsius the Elder, who ruled the Greek city state from 407 BC. After running up massive debts to pay for his military campaigns and lavish lifestyle, had a cunning plan to force his citizens to hand over their one drachma coins whereupon he re-stamped them as two-drachma coins. This strategy, of course, simply created inflation, and halved the value of the two drachma coin, reducing it back to its original real value! What probably irks ordinary Greeks the most in 2015 is that, this time around, after avoiding taxes for so long wealthy Greeks have been flocking to London leaving them to experience real hardship, and poverty and inequality levels more consistent with less developed economies.

Critics of the anti-austerity movement will point to the recent, if modest, return to growth seen in later 2014 and early 2015, but this is more likely to be the ‘dead cat bounce’ effect – even a dead cat will bounce if dropped from a great enough height! The lack of real growth means that tax revenues have remained weak and will continue to do so. This means that the ‘best party in town’ is perceived to be the one which returns Greece to its pre-debt situation – namely a speedy renegotiation of debt repayments rather than prolonging the pain any further.