Exchange_rate_policy

Exchange rate policy

The exchange rate of an economy affects aggregate demand through its effect on export and import prices, and policy makers may exploit this connection.

Deliberately altering exchange rates to influence the macro-economic environment may be regarded as a type of monetary policy. Changes in exchanges rates initially work there way into an economy via their effect on prices.

For example, if £1 exchanges for $1.50 on the foreign exchange market, a UK product selling for £10 in the UK will sell for $15 in New York. If the exchange rate now appreciates, so that £1 buys $1.60, the UK product in New York will now sell for $16. Assuming that demand in New York is price inelastic, this is good news for UK exporters because revenue in USDs will rise. However, if demand is elastic in New York, the effect of the appreciation of sterling would be damaging to UK exporters.

If the UK also imports goods from the USA, the rise in the exchange rate would mean that a $10 US product is now cheaper in London, falling from £6.67p to £6.25p. Importers do relatively well from the appreciation of the pound, in that the cost of imported raw materials or finished goods falls.

Therefore, whenever the exchange rate changes there will be a double effect, on both import and export prices. Changes in import and export prices will lead to changes in import and export volumes, causing changes in import spending and export revenue.

Exchange rates can be manipulated so that they deviate from their natural equilibrium rate. To stimulate exports, rates would be held down, and to reduce inflationary pressure rates would be kept up. While the Bank of England does not specifically target the exchange rate, the Monetary Policy Committee (MPC) will take exchange rates into account. Clearly, the MPC would prefer a relatively high rate, as this reduces the price of imports and works against inflationary pressure. However, the MPC must keep an eye on export competitiveness, and, if rates rise excessively, UK exports will become uncompetitive.

How exchange rates are manipulated

Exchange rates can be manipulated by buying or selling currencies on the foreign exchange market. To raise the value of the pound the Bank of England buys pounds, and to lower the value, it sells pounds. Rates can also be manipulated through interest rates, which affect the demand and supply of Sterling via their effect on inflows of hot money. Altering exchange rates is commonly regarded as a type of monetary policy.

Effects of a reduction in the exchange rate

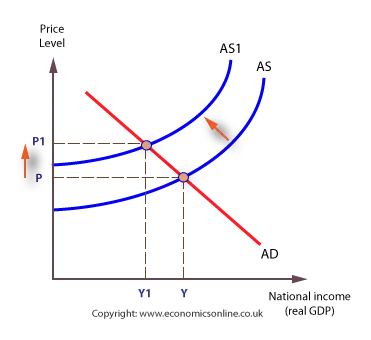

Assuming the economy has an output gap, a reduction in the exchange rate will reduce export prices, and, assuming demand is elastic, export revenue will increase.

A fall in the exchange rate will also raise import prices, and assuming elasticity of demand, import spending will fall. The combined effect is an increase in AD and an improvement in the UK balance of payments.

Cost push inflation

A fall in the exchange rate is inflationary for a second reason – the cost of imported raw materials adds to production costs and creates cost-push inflation.

Evaluation of exchange rate policy

The main advantage of manipulating exchange rates is that, because a large share of UK output is traded internationally, changes in exchange rates will have a powerful effect on AD. For example, lowering exchange rates, called devaluation, can:

- Raise aggregate demand

- Increase national output (GDP)

- Create jobs, amplified through the multiplier effect

- In addition, assuming the demand for imports and exports are price sensitive (price elastic), devaluation will lead to an improvement in the balance of payments – although this can also lead to inflation

Alternatively, raising exchange rates (revaluation) can:

- Help reduce excessive aggregate demand

- Keep inflation down

- Although the export sector may suffer and jobs might be lost

On balance, UK policy makers in recent years have preferred to allow the financial markets to determine exchange rates, rather than manipulate them for policy objectives. The last time exchange rates were directly targeted was between 1985 and 1992, when the UK shadowed movements in the Deutschmark, and then, from 1990 to 1992, when the UK became a member of the exchange rate fixing Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM).

See recent Sterling rate against the US Dollar and Euro